Governments set rules; businesses operate by following these rules. This idealized notion of political economy is more inaccurate today than ever before. Business leaders, including technology entrepreneurs, must participate in rulemaking due to deregulation and liberalization, prominent global risks (such as climate change and migration) that do not respect national borders, and digital technology that is spewing new issues requiring new rules. Business leaders are expected to be corporate diplomats.

Corporate diplomacy is not about turning businessmen into part-time politicians or statesmen. Rather, it involves corporations taking part in creating, enforcing, and changing the rules of the game that govern the conduct of business. It goes well beyond delegating external communications and lobbying to a public relations agency or a law firm. Precise understanding of corporate diplomacy would help businesses compete more effectively in the global economy. This column clarifies corporate diplomacy, its benefits and challenges.

Corporate Diplomacy: Taking Stock of History

Many formal rules govern the conduct of business. National regulators enforce rules: in the U.S., the Patent and Trademark Office grants intellectual property rights, the Internal Revenue Service administers tax rules, and the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice impose rules on mergers and acquisitions. Other countries have similar regulators. In order to deal with cross-border business activities, national regulators create international treaties to mutually recognize each other’s rules, and establish international organizations to harmonize rules. The world is far from flat, however. General Electric encountered this when its 2001 plan to acquire Honeywell was approved by the U.S. regulators, but faced fierce opposition from the European Commission. The enforcement of competition policy differs from country to country.

The recent history of liberalization and globalization points to the rising importance of corporate diplomacy. Since the end of the Cold War, national governments lost autonomy in a globalizing economy. They are sharing powers with businesses, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations.1 There is a steady decline in corporate income taxes, from 49.1% in 1981 to 32.5% in 2013 on average in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. States reduce taxes to make their locations more attractive to foreign direct investment, but in the process render themselves less resourceful to solve social problems. Business corporations engage in ‘regime shopping’ before choosing locations. Tax breaks raise public expectations that businesses will help solve societal problems. Civil society creates the rules of the game on ‘fair taxes,’ not government or business alone. Public protests against tax avoidance caused Google to pay the U.K. government £20 million in voluntary taxes in December 2012. This was a climb down by Google CEO Eric Schmidt, who earlier said that paying less tax was “just capitalism.” Businesses that fail to engage proactively in corporate diplomacy are criticized and cannot establish their legitimate role in society.

The recent history of liberalization and globalization points to the rising importance of corporate diplomacy.

This is not just a phenomenon of the past few decades. Corporate diplomacy has always been important in some locations. National borders are a fairly recent human invention. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 created the basis for national self-determination and sovereignty, and throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the Hudson Bay Company in North America and the East India Companies in India operated as company-states. They had authority to acquire territory, coin money, maintain forts and armies, make treaties, and administer justice. These functions of the state were carried out by private companies before colonial administration took over. Establishing and maintaining this took corporate diplomacy.

Corporate Diplomacy Hotspots

History gives pointers to corporate diplomacy opportunities and challenges. Corporate diplomacy matters irrespective of whether governments are present or absent. Governments present in regulated industries require corporations to seek license to operate and to comply with standards. Energy, mining, and infrastructure are good examples of such sectors, and companies in them have strong government affairs departments. Such sectors often are seen to embody national interest, and corporate diplomacy with host country governments is vital. The distinction between diplomacy and corporate diplomacy can be blurred. In 2013, Argentina expropriated the assets of Repsol YPF, the Argentinian subsidiary of the Spanish oil company. The Spanish parent used diplomacy with the government of Spain to pressure the government of Argentina for compensation. The failure of the Chinese oil company CNOOC to acquire the U.S. company Unacol in 2005 was due in part to failed corporate diplomacy when the U.S. Congress framed this acquisition as the Chinese state acting behind CNOOC. The company learned its lesson and successfully acquired Nexen in Canada. Through corporate diplomacy, both YPF and CNOOC reframed existing rules on national security.

Where governments do not exist, or have withdrawn (for example, via privatization or outsourcing) rule making and rule enforcement by businesses are also important. Government outsourcing3 is rife with corporate diplomacy. Business corporations such as G4S and Serco bid for and negotiate the terms of the outsourcing contracts, and engage in subtle but important corporate diplomatic work to create rules to define the respective responsibilities of the government and the private sector. For example, rules on decent treatment of detainees and asylum seekers are prescribed in international human rights law, the signatories of which are nationstates. Yet, when a government outsources the management of immigration detention services to private sector firms, as the Australian government has done, those firms become responsible de facto for enforcing the law.

Corporate Diplomacy in the Digital Economy

Digital technology creates a significant corporate diplomatic hotspot. Information and communication technologies have challenged existing rules for intellectual property, privacy, and data security. It has also challenged competition policy with network externalities, giving rise to charges of monopolistic behaviors by Microsoft, Amazon, and Google. No wonder, lobbying by corporate America has spread from the old economy to the new economy. In 2012, Google was the second biggest corporate lobby in Washington D.C., spending $18.2 million. (GE was first, spending $21.4 million.4) Technology firms now have a significant presence in Washington, D.C. Corporate diplomacy has become important in this sector.

Technology startups used to disregard corporate diplomacy. Uber started in 2010 offering an online chauffeur service that enabled customers to book a ride quickly using a mobile device. Uber did not own the cars but contracted with private car owners and drivers. Uber was neither a taxi service nor a limousine service. Its business did not fit the conventional regulatory framework that usually regulated taxis and limousines separately. Uber often ignored regulations in a city and just started operations to avoid lengthy regulatory approvals. It built a presence and proved its value to users, relying on citizen support for its commercial success. It is useful to explore the case of Uber to see why and how corporate diplomacy became important.

It is useful to explore the case of Uber to see why and how corporate diplomacy became important.

Peer-to-peer collaboration can make consumer choice and sovereignty paramount. Uber and other companies claim that the “sharing economy” they are building can self-regulate. Consumers ‘vote with their money’, making regulatory oversight redundant. Ratings by users are a transparent self-regulatory mechanism to make the market function well. Irrespective of whether these claims are true, service professions (including medical, legal, financial) have self-regulation that operates in the shadow of government regulation to be effective. Self-regulating professions operate only as long as they are seen to be acting as trustees of public interest. Ignoring governments is not sustainable.

Uber’s growth has been impressive: it now operates in over 300 cities in 67 countries. However, it failed to thwart bans or partial bans in cities in Australia, Germany, India, and Thailand. In 2015, Uber hired David Plouffe (political strategist and former campaign manager for President Obama) and Rachel Whetstone (Google’s head of communications), to boost the company’s public policy team and to maximize smooth sailing with city regulators. Uber’s political strategy must deal with important vested interests, notably licensed taxi drivers. Consumer groups who benefit from more convenient and cheaper rides can help thwart bans. Supporting the green ‘low emission’ agenda of some cities can help as well. Corporate diplomacy is required to manage these stakeholders.

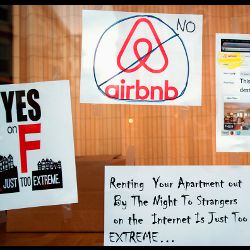

Because of experiences like this Silicon Valley startups are taking corporate diplomacy seriously. Uber, Airbnb, and other firms with the “sharing economy” business model must create new rules of the game. It is better to influence the creation of new rules proactively than have inimical rules imposed.

Conclusion

Many people might agree with Ronald Reagan’s quip “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.'” Efforts to keep the government at bay can create a blind spot with respect to corporate diplomacy.

Business leaders must negotiate with governments to influence rules that affect their environment to their advantage. In doing so, they do well to recognize that as corporate diplomats, they establish norms that legitimize the conduct of business. Thus, business leaders participate in building institutions, which are both formal rules and social norms.2

Corporate diplomacy happens in areas where governments are present as regulators, service providers, and owners of assets. Corporate diplomacy is equally needed where governments are absent due to deregulation or weak law enforcement capacity. It is also required in new markets with new technology where rules are yet to be made. Creating new rules requires tactics somewhat different from conventional lobbying. Corporate diplomacy is a mind-set that sees the role of business as working with governments to create societal rules that govern the conduct of business. Corporate diplomats should not scare public officials by stating: “I’m from the corporation and I’m here to help.” Keeping governments at bay does not guarantee business success, nor will keeping corporations at bay lead to successful regulation. Corporate diplomacy is a promising way forward for understanding how to create and change rules for better outcomes.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment